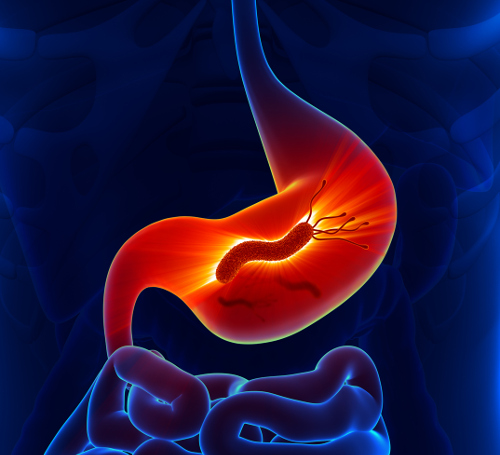

Credit: iStock.com/decade3d

What is H. pylori? Helicobacter pylori, or H. pylori, is a type of bacteria that mainly targets the stomach area, specifically the stomach lining and duodenum (the upper-portion of the small intestine). H. pylori infection can lead to a number digestive issues, including gastritis, ulcers, and maybe even stomach cancer.

The bacteria typically enter the body during childhood, and settle in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Experts estimate that anywhere between half and two-thirds of the human population carries the bacterial invaders.

Although most will experience no symptoms, H. pylori infection does seem to have long-term implications for the body’s immune system. However, there are some ways to treat the condition through dietary and lifestyle changes, including probiotics and natural herbal remedies.

In this article:

- H. Pylori Infection Causes

- H. Pylori Infection Symptoms

- H. Pylori and Cancer

- H. Pylori and Autoimmune Disease

- H. Pylori Risk Factors

- H. Pylori Diagnosis

- H. Pylori Treatment

- Natural Remedies for H. Pylori Infections

- Tips to Prevent H. Pylori Infection

- H. Pylori Infection Is Both Treatable and Preventable

H. Pylori Infection Causes

There are no definitive answers regarding H. pylori causes, but a few factors may be connected to outbreaks of the bacteria.

It appears that H. pylori bacteria enter your body through the mouth. This can happen through the transfer of saliva from someone who is already infected to another individual, or through contact with contaminated water or food. The bacteria can also live in feces, so the risk of contamination and infection goes up in areas where sanitary conditions are not very high: developing countries, housing where many people live within a relatively small space, and regions without a reliable supply of drinking water or hot water.

Once the bacterium enters your mouth, it will find its way to your stomach. Once there, it secretes an enzyme called urease, which helps neutralize the acidity of your stomach acid, allowing the bacteria to survive the environment of the stomach long enough to burrow into the stomach lining.

Being entrenched in the stomach lining makes it harder for the body’s natural defenses to attack the bacteria. Most sufferers pick up H. pylori bacteria during their childhood—children are less likely to wash their hands thoroughly after using the bathroom or before eating—but it is not impossible to contract the infection as an adult. That being said, bacteria picked up in childhood may not produce symptoms for a number of years.

H. Pylori Infection Symptoms

The majority of people infected with the bacteria don’t actually show H. pylori symptoms, as many are resistant to it. Children’s underdeveloped immune systems may be partly why they are more likely to be infected than adults. Unfortunately, it is unknown why some people, both young and old, have a resistance and others do not.

For those who are affected by the bacteria, symptoms can include the following:

- Ache or burning pain in your abdomen

- Abdominal pain that worsens when your stomach is empty

- Nausea

- Loss of appetite

- Frequent burping

- Bloating

- Unintentional weight loss

In severe cases, you may also experience:

- Severe or persistent abdominal pain

- Difficulty swallowing

- Bloody or black colored stools

- Bloody or black vomit.

If you start to see severe symptoms, you should see a doctor as soon as possible. Many of the more serious symptoms are the result of an ulcer.

H. pylori bacteria attack the stomach lining and weaken it. The lining of your stomach is what usually protects your stomach from its own acid. When that lining is weakened, the acid can inflict damage causing stomach ulcers. In fact, H. pylori are the most common cause of gastric ulcers.

Unfortunately, those ulcers can sometimes begin to bleed, which can lead to the blood in your stool and vomit.

H. Pylori and Cancer

One of the possible serious health complications for people infected with H. pylori is stomach cancer. Those who are infected are approximately eight times as likely to develop stomach and other gastric cancers as those without an H. pylori infection.

The actual connection between H. pylori and cancer is unclear, but there are a few theories. The American Cancer Society proposes that it may have to do with the ulcers and other biological changes that H. pylori can bring to the stomach. These may also make the stomach a prime target for cancer growth.

It should be noted that while people with H. pylori infection are more likely to develop stomach cancer, not everyone that has the bacteria will fall victim to the disease. Stomach cancer in general isn’t as prevalent in North America as it once was, but is still a concern in third-world countries, areas with poor sanitation, and where multiple people and families share small living areas—the same type of conditions H. pylori thrives in.

In a strange twist, H. pylori may also play a role in decreasing the chances of cancer in the esophagus. As we noted previously, the bacteria can decrease the effectiveness of stomach acid, especially if the infection has been going on for a number of years. This decrease in the acidity of stomach acid could reduce the amount of acid reflux episodes (where stomach contents come back up into the esophagus). This, in turn, decreases the amount of damage stomach acid can do to the esophagus and the chances of cancer developing in that area.

H. Pylori and Autoimmune Disease

Infection with H. pylori increases the risk of developing gastric cancers, but recently, attention has been drawn to the possible connections between the bacteria and autoimmune diseases.

An autoimmune disease occurs when an overactive immune system attacks and damages its own tissues. Scientists believe that the disease develops due to a combination of environmental triggers and genetic predisposition.

Many research studies have pointed to H. pylori as a possible stimulant in cases of stomach-related autoimmunity, but there is also some evidence that the bacteria may trigger certain autoimmune diseases that impact organs outside of the stomach region.

Chronic Inflammation

One theory suggests that H. pylori bacteria can send the body into an ongoing inflammatory state. This chronic inflammation may cause continuous antigenic stimulation, where your body begins creating antibodies to defend itself against invaders. Only the body has mistakenly identified itself as the enemy.

Molecular Mimicry

Another theory suggests that H. pylori bacteria are biologically similar to other components of internal organs and cells of the body. This accidental mimicry causes the body to send antibodies to attack not only the bacteria, but also the internal organs and their components. This theory is usually linked to organ-specific disorders like Hashimoto’s disease (where the immunes system attacks the thyroid), and non-organ specific autoimmune disorders like idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (the immune system attacks the platelets in the bloodstream), and rheumatoid arthritis (where the immune system attacks the lining of the membranes that surround your joints called the synovium).

The scientific evidence has been inconclusive, as there are reports both in support of and against H. pylori as a cause of autoimmune diseases.

There are also autoimmune diseases like lupus, where there isn’t sufficient evidence to say that H. pylori bacteria prompts the disease, but there is evidence to support the case that most sufferers of lupus tend to also have also issues with H. pylori infections.

H. Pylori Risk Factors

Individuals appear to have an increased risk of contracting the following medical conditions with an H. pylori infection.

1. Upper Respiratory Tract Infections

Those suffering from an H. pylori infection have a greater chance of developing upper respiratory tract infections. The bacteria can live within gastric juices. If those juices reach the esophagus through conditions like acid reflux, or GERD, the bacteria in the acid can stay alive in your esophagus and may cause or contribute to an infection of the voice box (larynx), throat, mouth, nasal cavity, or nostrils.

2. Sinus Infections

Sinus infections may also have connections to H. pylori. In some people suffering from sinus infections, the bacteria can often be detected in nasal polyps, as well as mucus and the inflamed areas of the sinuses. This leads some researchers to believe that H. pylori may cause or contribute to sinus infections.

3. Adenoiditis

Acute or chronic inflammation of the adenoids (or pharyngeal tonsils) has also been linked to H. pylori bacteria. Just as how upper respiratory tract infections may develop, this inflammation may be triggered by bacteria that come up with gastric juices and remain in the esophagus, helping to aggravate the adenoids.

Lifestyle risk factors may include smoking and consumption of meat, restaurant food, and unfiltered water.

H. Pylori Diagnosis

A few tests are used in order to diagnose H. pylori infection.

1. Blood Sample

A simple blood sample test may be able to tell you whether H. pylori bacteria are currently or have previously been present in your system. Unfortunately, blood tests are not 100% reliable when it comes to the bacteria, and other tests may be necessary.

2. Breath Test

The breath test for H. pylori detection is rather simple. The doctor will give you a liquid or pill that contains tagged carbon molecules. When the pill dissolves in your stomach, the solution is released if the bacteria are present.

The body then absorbs the carbon and expels it when you breathe out. Upon exhaling into a bag, the doctor will use a specialized device to detect if there is any carbon in the breath and confirm the presence of H. pylori.

Acid-suppressing drugs like proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) and antibiotics can interfere with breath test results, so a doctor will probably ask you to stop taking them a week or two before the scheduled test for a clearer result.

3. Stool Sample

As noted, H. pylori bacteria can survive in the stool of someone who is infected for a good period time (hence why it is one of the bacteria’s best vehicles of transmission). Doctors can look for signs of the bacteria in your stool sample. Similarly to the breath test, PPIs and bismuth subsalicylate can also affect the test results. You will be asked to stop using them for the week or two preceding the test.

4. Upper Endoscopy Exam

For this test, you will need to be sedated. An endoscope, a long, small tube that is equipped with a camera and small tools for taking samples, will be passed down your throat and into your stomach. With this, the doctor can take a look for evidence to support an H. pylori infection, like ulcers, as well as take samples.

Once extracted, the samples can be tested for the presence of the bacteria.

H. Pylori Treatment

Medical treatment for H. pylori bacteria is a multistep process that involves a few different medications at the same time. One medication will help to reduce stomach acid production. Reducing the levels of stomach acid will allow the bacteria-killing antibiotics and other medications a greater impact on the infection. This antibiotic and acid-reducing mixture is often referred to as the “triple therapy.”

Drugs that can help reduce your stomach acid may include dexlansoprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, or rabeprazole.

In addition to medication to help reduce stomach acid, you will be prescribed antibiotics— usually two different kinds. H. pylori bacteria can be difficult to root out due to the way they burrow into the stomach lining. Two separate antibiotics could work together to help dig the bacteria out and neutralize it.

Antibiotics that may be prescribed are amoxicillin, clarithromycin, metronidazole, tetracycline, or tinidazole. Doctors often recommend bismuth subsalicylate alongside the antibiotics to help clear out the infection.

During the H. pylori treatment process, you may end up taking upwards of 14 pills a day for a few weeks. It is important to finish the medical treatment due to the bacteria’s resiliency. It is fairly common for a doctor to retest your stool or breath at the end the treatment, to make sure that the treatment was effective and the bacteria is gone.

There is some testing currently being done in the field of phototherapy. Phototherapy is the use of ultra-violet (UV) light to treat different medical conditions. In this case, the UV light is meant to kill the H. pylori bacteria. In trial studies, researchers created endoscopes that were fitted with UV light sources. The endoscope is guided into the stomach of the person with the H. pylori infection. This is meant as an alternative form of treatment if antibiotics are not an option.

Natural Remedies for H. Pylori Infections

Prescription medications like acid neutralizers and antibiotics have been proven effective for eliminating the bacterial infection. However, due to the potential negative side effects and increasing antibiotic resistance among bacteria, you may be looking for ways to treat H. pylori naturally. Researchers have discovered a number of natural solutions that may work for you.

1. Probiotics

Probiotics are often referred to as “good bacteria” for your stomach, and numerous studies suggest that certain strains of probiotics may be able to eradicate H. pylori from the region. A study published in Inflammation and Allergy Drug Targets in 2012 showed that 13 out of 40 of the patients using an eight-strain probiotic supplement were H. pylori free by the end of the trial. Probiotics also won’t interfere with antibiotics, so they may be able to help the antibiotics perform their job as well. Probiotic strains that appear particularly adept at battling H. pylori bacteria include Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus casei, and Lactobacillus brevis.

2. Nigella Sativa

Nigella sativa, or black seed, may be able to help you treat H. pylori infections in combination with an acid blocker. Black seed possesses antibacterial qualities that, according to research released in 2010, has very good anti- H.pylori activity. The study, published in the Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology, found that using two grams of ground black seeds daily along with omeprazole (a commonly prescribed acid blocker) could be as potent as the “triple therapy” technique.

3. Broccoli Sprouts

Broccoli sprouts are broccoli that is only a few days old, and hasn’t matured into a full plant yet. These sprouts contain a chemical called sulforaphane, which has a many antioxidant benefits, seemingly including fighting H. pylori bacteria. Research conducted for Digestive Diseases and Sciences discovered that seven out of nine test subjects who consumed broccoli sprouts (either 14, 28, or 56 grams) twice a day, for a week, ended up testing negative for H. pylori at the end of the seven days. Six of the subjects still tested negative 35 days into the study.

4. Green Tea

Green tea has long been used as a medicinal drink due to its antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties. Green tea contains catechins, which could not only possibly prevent H. pylori infection, but they may be able to treat it as well. Essentially, the green tea may help prevent stomach lining inflammation if ingested prior to exposure to Helicobacter infection, and it may be able to continue to help after exposure to the bacteria has occurred.

5. Garlic

Garlic contains a compound called allicin, which gives garlic some wonderful antibiotic properties that seem to be able to work against H. pylori bacteria. Eating two cloves of garlic (approximately three grams a day at lunch and dinner) by adding them to food or just eating them raw, could help destroy H. pylori as well as help prevent it.

6. Propolis and Honey

Propolis, otherwise known as bee glue, is the sticky mixture of bee saliva and beeswax that is used as a sealant by the bees to close off spaces within their hives. This bee glue contains over 300 compounds, including amino acids, coumarins, phenolic aldehydes, polyphenols, sesquiterpene quinones and steroids. Within this combination of compounds is a mixture of phenolic compounds that could help reduce H. pylori growth. Honey is made from similar materials and may also be of help in getting rid of the bacteria.

7. Olive Oil

According to Spanish researchers at the Instituto de la Grasa and the University Hospital of Valme, olive oil’s antibacterial abilities may be able to help to fight H. pylori bacteria. In a 2007 study, the Spanish team found that olive oil was able to remain stable in gastric acid and have an effect on eight different strains of H. pylori bacteria, including three strains that were antibiotic resistant.

8. Licorice Root

Licorice root may be able to help prevent infection, as well as give the bacteria trouble staying in the stomach. Licorice root contains aqueous extracts and polysaccharides that are anti-inflammatory in nature. While they are often used for treatment of stomach ulcers, those same compounds could prevent the H. pylori bacteria from sticking to cell walls. This might help prevent the bacteria from digging into the stomach wall lining and help flush it out of the lining. This alone will not kill the bacteria, but it might make it much easier for other treatments to reach the bacteria and do greater damage.

Tips to Prevent H. Pylori Infection

There are various changes you can make to your diet and lifestyle that may prevent H. pylori infections.

Changes to Diet

Several dietary changes could help you avoid a H. pylori infection. There are certain foods to eat as well as foods you should avoid. Foods to include are:

- Probiotic-rich foods like kefir

- Foods rich in omega-3s, like salmon, flax seed, and chia seed

- Raw honey (Manuka honey is particularly good) due to its antibacterial properties

- Berries that are high in antioxidants, like raspberry, strawberry, blackberry, blueberry and bilberry

- Broccoli and broccoli sprouts

Foods to avoid include:

- Caffeine (caffeine can help increase stomach acid activity)

- Carbonated beverages

- Pickled foods

- Spicy foods

- Low-fiber grains

There are also some herbs that could help inhibit the growth of the bacteria like Agrimonia eupatoria, goldenseal, meadowsweet, and sage.

Hygienic Living Conditions

H. pylori infection is a bigger problem in developing countries than it is in the West. Part of that is due to poor sanitary conditions. One of the easiest ways to avoid the bacteria is to avoid unhygienic environments. Have a safe base of drinking water, avoid places with poor sanitation, and maintain good hygiene by washing your hands, especially after using the washroom due to possible fecal contamination.

H. Pylori Infection Is Both Treatable and Preventable

H. pylori bacteria are widespread in the lives of many people, making it difficult to avoid contracting an infection. The bacterium can be spread orally, and through contact with contaminated food, water, or fecal matter.

For most affected individuals, the bacteria will not produce any symptoms. In others, the bacteria may lie in the digestive tract for a number of years before any health issues arise. And make no mistake—the issues that can arise from H. pylori infection can be very serious, ranging from painful stomach ulcers to cancers of the GI tract.

But, there are ways to treat H. pylori infection both medically and naturally, according to recent research. Hopefully, you now know how to recognize the symptoms, seek proper diagnosis and treatment, and avoid the more severe complications.

Related Articles

Is H. Pylori Contagious? Diagnosis and Prevention Tips

Sources

“Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection,” Mayo Clinic, http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/h-pylori/home/ovc-20318744, last accessed August 25, 2017.

“What Is H. pylori?” WebMD, http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/h-pylori-helicobacter-pylori#3-7, last accessed August 25, 2017.

Colledge, H., Cafasso, J., “H. pylori Infection,” Healthline, http://www.healthline.com/health/helicobacter-pylori#overview1, last accessed October 13, 2015.

Rahul M., et al., “Assessment of Risk Factors of Helicobacter Pylori Infection and Peptic Ulcer Disease,” Journal of Global Infectious Diseases, Apr. 2013; 5(2): 60–67; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3703212/, last accessed August 25, 2017.

Kariya, S., et al., “An association between Helicobacter pylori and upper respiratory tract disease: Fact or fiction?” World Journal of Gastroenterology, Feb. 2014; 20(6): 1470–1484; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3925855/, last accessed August 25, 2017.

Mabe, K., et al.,, “In vitro and in vivo activities of tea catechins against Helicobacter pylori,” Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Jul. 1999; 43(7):1788-91; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10390246, last accessed August 25, 2017.

Stoicov, C., et al.,, “Green tea inhibits Helicobacter growth in vivo and in vitro,” International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, May 2009; 33(5):473-8; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19157800, last accessed August 25, 2017.

Yanaka, A., “Role of Sulforaphane in Protection of Gastrointestinal Tract against H.pylori- and NSAID-Induced Oxidative Stress,” Current Pharmaceutical Design, Feb. 2017, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28176666, last accessed August 25, 2017.

Galan, M., et al.,“Oral broccoli sprouts for the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: a preliminary report,” Digestive Diseases and Sciences, Aug. 2004; 49(7-8):1088-90; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15387326/, last accessed August 25, 2017.

Salem, E., et al., ”Comparative Study of Nigella sativa and Triple Therapy in Eradication of Helicobacter pylori in Patients with Non-Ulcer Dyspepsia,” The Saudi Journal of Gastroenterology, Jul. 2010; 16(3): 207–214; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3003218/, last accessed August 25, 2017.

Rosania, R., et al., “Probiotic multistrain treatment may eradicate Helicobacter pylori from the stomach of dyspeptics: a placebo-controlled pilot study,” Inflammation & Allergy Drug Targets, Jun. 2012; 11(3): 244-9; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22452604, last accessed August 25, 2017.

McDermott, A., “Natural Treatment for H. pylori: What Works?” Healthline, August 10, 2016; http://www.healthline.com/health/digestive-health/h-pylori-natural-treatment#overview1, last accessed August 25, 2017.

Wittschiera, N., et al., “Aqueous extracts and polysaccharides from Liquorice roots (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) inhibit adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric mucosa,” Journal of Ethnopharmacology, Sep. 2009, 125(2): 218-23; http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378874109004371, last accessed August 25, 2017.

Lembo, A., et al., “Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection with Intra-Gastric Violet Light Phototherapy – a Pilot Clinical Trial,” Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, Jul. 2009; 41(5): 337–344; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2841969/, last accessed August 25, 2017.

Baltas., N., et al., “Effect of propolis in gastric disorders: inhibition studies on the growth of Helicobacter pylori and production of its urease,” Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry, 2016; 31(sup2):46-50; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27233102, last accessed August 25, 2017.

“Bacteria that can lead to cancer,” American Cancer Society, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/infectious-agents/infections-that-can-lead-to-cancer/bacteria.html, last accessed August 25, 2017.

“Helicobacter pylori and Cancer,” National Cancer Institute, https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectious-agents/h-pylori-fact-sheet#q3, last accessed August 25, 2017.